What is it about the novel Christy and the program based on the novel

that draws so many readers and viewers into the love story between a common

mountain doctor and a young schoolteacher who leaves her family and Asheville

home for, of all things, a teaching position? Certainly young teachers have

married doctors before. Certainly we have all seen many romances between

beautifully matched couples replicated time and time again in print and film.

Even in my own experience, I accepted a teaching position once in a rural

area and married a man whose last name comes somewhat close to a true

sounding Scottish name. Alas, but even true experience falls short of

romance such as that of Christy Huddleston and her doctor, Neil MacNeill. What

is it about this novel and the romance then that stirs up so much interest

and willingness to write and talk about it?

For women, the young Christy represents to us a version of ourselves who

once had a claim to youth and beauty (if only speaking for myself), but also

an inexperience that made us both vulnerable and willing to learn freely from

whatever sources and people who crossed our paths. In youth, certain people,

events, and remarks made by others seem so important in our becoming the

women we and our family hope we become. Youth makes us impressionable and

the lack of experience makes us yearn to learn from those we see as good

around us. Without undue length, fans of Christy can count numerous times

Christy sought her opportunity to learn from all around her, Fairlight

Spencer, Miss Alice, Dr. MacNeill, the Cutter Gap children, and even the

mountains.

For women, the young Christy represents to us a version of ourselves who

once had a claim to youth and beauty (if only speaking for myself), but also

an inexperience that made us both vulnerable and willing to learn freely from

whatever sources and people who crossed our paths. In youth, certain people,

events, and remarks made by others seem so important in our becoming the

women we and our family hope we become. Youth makes us impressionable and

the lack of experience makes us yearn to learn from those we see as good

around us. Without undue length, fans of Christy can count numerous times

Christy sought her opportunity to learn from all around her, Fairlight

Spencer, Miss Alice, Dr. MacNeill, the Cutter Gap children, and even the

mountains.

In this classic sense, Christy Huddleston appeals to readers like every

other Bildungsroman character from fiction ever has. A Bildungsroman

character is usually a youth who grows mentally, spiritually, or emotionally

during the events of his life or during the course of the novel in which he

appears. Hundreds of novels portray this type of character, and these types

of characters are the staple of a child's school reading assignments (Huck

Finn, Anne Frank, Pip from Great Expectations). Readers have grown up

following the particular hazards and accomplishments of fictional youths,

hoping in their vicarious enjoyments to see their own pains and joys relived

in the fresh journey of a character's life. Only with Bildungsroman

characters like Christy can readers take the journey again as adults.

In fact, the journey with Christy from a young girl to a young woman

enables women to relive the pains associated with failed love and sometimes

disastrous relations within families and careers, and sometimes we enjoy the

bittersweet joys of circumstances that did go our way. In this manner, each

episode acts as a catharsis, an opportunity to relive and purge the struggles

of youth and remind us that our own growing process had its own special

validity, just as this young schoolteacher's. Every episode leaves viewers

and readers feeling fresher and more aware of whatever lesson they want to

draw from the journey of our heroine.

To establish the fact that Christy is a Bildungsroman character, readers

may view a number of instances that seem an on-going part of her growth. For

example, she is tested by the death of her special friend, Fairlight Spencer.

After Fairlight's death, Christy momentarily loses but regains her faith in

God, hopefully making her religious tie stronger. Additionally, she becomes

a better teacher simply through her experience and growing awareness of her

pupils' backgrounds and rectification of her student interactions that were

less than teacher-perfect. Readers need only remember the episode in which

Fairlight's daughter expressed jealousy and anger that a male student, whose

family did not feel college was viable anyway, received Miss Huddleston's

excessive attention and tutoring. This was an interesting program, to say the

least, since it raised questions about female education and student

motivation and background and how a teacher approached timeless classroom

issues. Lastly, Christy matures in her own awareness of love, finally

choosing, in her mind, the best partner from two choices. Unfortunately, all

her other areas of growth are overshadowed by this last area, but readers

should keep in mind that her marriage choice was her last choice in the

program and the novel, a choice that could not have ever been as good had she

not had the pre-requisite maturity in her mental and spiritual domains.

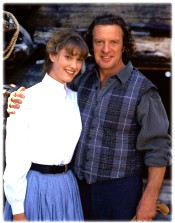

Finally, she and Dr. MacNeill complemented each other as partners because that

growth had to come to fruition, ironically for both of them.

Notice, readers, that a Bildungsroman character's physical growth is not

really a point of interest in this type of novel. Hence, the twenty year or

so age difference is actually irrelevant. Maturity is a matter of elements that

are developed as much as possible, not a sequential number of years that have

passed. For the sake of fiction, readers can be glad for Christy, for her

choice of a spouse was a decision made that would suit that of a mature

woman, not that of a young girl, for matrimonial years to come.

The second reason for the program's and novel's appeal is that the story

relates the tension between dual aspects of human nature, the physical and

spiritual. What better professions could Christy's potential mates have

chosen that would better represent both the physical and spiritual than that

of doctor and minister. Those readers of any of Nathaniel Hawthorne's works

may recognize that Hawthorne uses the same technique in his work, The Scarlet

Letter and some of his short stories. Obviously, Marshall's work reflects

some fictional circumstances, so Marshall may not have thematically paired

these two professions, but the effect is likewise noteworthy. Just as

Christy prolongs her decision as to which man to follow, her mission at

Cutter Gap seems to arouse feelings initially of her purpose there. Does she

choose to satisfy what she physically could secure at home, away from Cutter

Gap, or does she make physical sacrifices to secure a more philosophic

mission and dream at Cutter Gap? Obviously, physical comforts and wants were

secondary compared to the dream (i.e. a spiritual goal) she felt she could

fulfill. As said earlier, her being torn between these two lovers is an echo

of the same physical vs. spiritual struggle she endures career-wise. But what

Christy chooses is not entirely the physical or spiritual side of her nature

but a balance of the two aspects. And it is with MacNeill that she finds this

balance.

The second reason for the program's and novel's appeal is that the story

relates the tension between dual aspects of human nature, the physical and

spiritual. What better professions could Christy's potential mates have

chosen that would better represent both the physical and spiritual than that

of doctor and minister. Those readers of any of Nathaniel Hawthorne's works

may recognize that Hawthorne uses the same technique in his work, The Scarlet

Letter and some of his short stories. Obviously, Marshall's work reflects

some fictional circumstances, so Marshall may not have thematically paired

these two professions, but the effect is likewise noteworthy. Just as

Christy prolongs her decision as to which man to follow, her mission at

Cutter Gap seems to arouse feelings initially of her purpose there. Does she

choose to satisfy what she physically could secure at home, away from Cutter

Gap, or does she make physical sacrifices to secure a more philosophic

mission and dream at Cutter Gap? Obviously, physical comforts and wants were

secondary compared to the dream (i.e. a spiritual goal) she felt she could

fulfill. As said earlier, her being torn between these two lovers is an echo

of the same physical vs. spiritual struggle she endures career-wise. But what

Christy chooses is not entirely the physical or spiritual side of her nature

but a balance of the two aspects. And it is with MacNeill that she finds this

balance.

As seeing how Christy makes her decision for Dr. MacNeill both in book

and film, I realize now the progression of their relationship. As a couple,

they ultimately struck a balance between the physical and spiritual. In

fact, the doctor's praying to God and accepting God's role in his life and

Christy's completed him and "healed" him. Because of his scientific training

and mountain experiences, he previously mistrusted miracles and

spirituality, especially being so grounded in the physical reality of his

region and disease-susceptible bodies of its community. His conversion,

which is beautifully portrayed in book and film, made him a more fit partner

in the relationship. He had been so fixed in the physical environment and a

perspective that only considered physical truths, but the crisis of Christy's

sickness provides him a chance to add a spiritual dimension to his life.

Christy choosing a partner without spirituality would be hard to imagine and

seem even unfit considering her choice to teach at a Christian missionary.

Hence, David Grantland, the minister, always seemed the perfect match. So,

why wasn't he?

As seeing how Christy makes her decision for Dr. MacNeill both in book

and film, I realize now the progression of their relationship. As a couple,

they ultimately struck a balance between the physical and spiritual. In

fact, the doctor's praying to God and accepting God's role in his life and

Christy's completed him and "healed" him. Because of his scientific training

and mountain experiences, he previously mistrusted miracles and

spirituality, especially being so grounded in the physical reality of his

region and disease-susceptible bodies of its community. His conversion,

which is beautifully portrayed in book and film, made him a more fit partner

in the relationship. He had been so fixed in the physical environment and a

perspective that only considered physical truths, but the crisis of Christy's

sickness provides him a chance to add a spiritual dimension to his life.

Christy choosing a partner without spirituality would be hard to imagine and

seem even unfit considering her choice to teach at a Christian missionary.

Hence, David Grantland, the minister, always seemed the perfect match. So,

why wasn't he?

The minister clearly possessed a claim to spirituality. Spirituality is, by no means, a weakness or a trait undeserving that of a marriage partner. The problem with Grantland is his lack of balance between his spiritual and physical side, a balance Christy and MacNeill discover for their

own. Grantland, perhaps because of his youth or lack of experience or even

personality seems void of any intimate knowledge of the people of Cutter Gap

and can not help them in a meaningful and physically close way. True, he

does help build a major road and tend the environs of the missionary, but he

never seems to be the one asked to "hurry" to the community's physical rescue

as the doctor is so often (a fact almost ridiculously portrayed in the film

"Choices of the Heart). Grantland delivers sermons for their souls' sake.

Likewise, Christy's relationship with him seemed more of a career move for

them both, a way to extend upon the dream and the missionary philosophy. Another observation of a low-brow type is that the episodes between the two depicted many sweet kisses, but plainly put, little physical passion that I am sure would be appropriate for teachers and ministers to enjoy during their off time. Their relationship almost

perfectly parallels that of Jane Eyre and her missionary cousin, St. John

Rivers from the novel Jane Eyre. Alas, Jane does not choose the minister

either but a darker more masculine and passionate man, Edward Rochester.

(Christy and Jane Eyre cry out for comparison.) All in all, both physical

and spiritual dimensions are satisfied with Christy's marriage decision.

The third and last reason for the novel's appeal is that it allows the

audience to witness the typical "rescue" and "healing" themes prevalent in

many classic love stories. One of eight typical love stories is one in which

one partner's attraction to the other is enhanced by an opportunity to rescue

the other. Stereotypically, the male often rescues the woman who is either

a. trapped b. despondent c. loveless d. lonely e. etc., I

argue that Christy reverses the typical pattern by having Christy be the

spiritual rescuer of Dr. MacNeill, literally because of her sickness but also

in an ongoing manner throughout the novel.

Is it in the female psyche to save or refurbish some needy male, too,

especially one whose needs so fit the missionary purpose? The minister,

unluckily,

needs no such help, (In fact, I have always found him patronizing.) so he

falls by the wayside. Of course, a reader's acceptance of this idea depends

on his

thinking about male and female roles. Secondly, the "healing" aspect of the

romance draws both Christy and some readers toward a preference for the

doctor as her marriage choice, although I was more relieved for the doctor

after his religious conversion than his marriage proposal. The doctor's

spiritual "healing"

parallels nicely with a literary concept termed the Greenworld, a convention

used much by Shakespeare in his pastoral romances. (I must credit the

webmaster of this site for this idea.)

The third and last reason for the novel's appeal is that it allows the

audience to witness the typical "rescue" and "healing" themes prevalent in

many classic love stories. One of eight typical love stories is one in which

one partner's attraction to the other is enhanced by an opportunity to rescue

the other. Stereotypically, the male often rescues the woman who is either

a. trapped b. despondent c. loveless d. lonely e. etc., I

argue that Christy reverses the typical pattern by having Christy be the

spiritual rescuer of Dr. MacNeill, literally because of her sickness but also

in an ongoing manner throughout the novel.

Is it in the female psyche to save or refurbish some needy male, too,

especially one whose needs so fit the missionary purpose? The minister,

unluckily,

needs no such help, (In fact, I have always found him patronizing.) so he

falls by the wayside. Of course, a reader's acceptance of this idea depends

on his

thinking about male and female roles. Secondly, the "healing" aspect of the

romance draws both Christy and some readers toward a preference for the

doctor as her marriage choice, although I was more relieved for the doctor

after his religious conversion than his marriage proposal. The doctor's

spiritual "healing"

parallels nicely with a literary concept termed the Greenworld, a convention

used much by Shakespeare in his pastoral romances. (I must credit the

webmaster of this site for this idea.)

The concept of the Greenworld applies to a story where characters leave

previous societies which were either too strict or lenient for the

characters' happiness. They establish themselves in a "green" world, so

called because that world is nature. Green, of course, is equated with nature

and its healing properties. Cutter Gap's mountains and rivers make up the

Greenworld of Christy and her fellow characters. It is a refuge away from

society at large. It is here they learn and recover from the ills of

prejudice, ignorance, cynicism....typhoid. The Greenworld idea applies

somewhat nicely, but it does not fit perfectly since Asheville's ills, if

any, are not addressed and Cutter Gap has its own share of unique problems.

Readers can recognize, however, that all characters seem improved by the end

of the novel, and Dr. MacNeill, especially, loses his cynical nature in the

glories of love, companionship, and literal nature. According to the

Greenworld idea, all characters, once healed, are entitled to return to the

previous society a better person. For the minister's sake, it is hard to

imagine him

healed but feeling a little bitter, maybe cynical of love and women. In that

case, he must remain in Cutter Gap until his true opportunity to grow, learn,

or be healed or rescued comes along! He may be the answer to Shakespeare's

Jacques (All's Well That Ends Well!), and may it be said that all does end

well for Dr. MacNeill. His marriage strongly affirms his connection to the

mission and his community. He can leave behind the desolation of his cabin

as it becomes a home, and his marriage, unlike his education, may unite him

to his community forever as well as to Christy.

The concept of the Greenworld applies to a story where characters leave

previous societies which were either too strict or lenient for the

characters' happiness. They establish themselves in a "green" world, so

called because that world is nature. Green, of course, is equated with nature

and its healing properties. Cutter Gap's mountains and rivers make up the

Greenworld of Christy and her fellow characters. It is a refuge away from

society at large. It is here they learn and recover from the ills of

prejudice, ignorance, cynicism....typhoid. The Greenworld idea applies

somewhat nicely, but it does not fit perfectly since Asheville's ills, if

any, are not addressed and Cutter Gap has its own share of unique problems.

Readers can recognize, however, that all characters seem improved by the end

of the novel, and Dr. MacNeill, especially, loses his cynical nature in the

glories of love, companionship, and literal nature. According to the

Greenworld idea, all characters, once healed, are entitled to return to the

previous society a better person. For the minister's sake, it is hard to

imagine him

healed but feeling a little bitter, maybe cynical of love and women. In that

case, he must remain in Cutter Gap until his true opportunity to grow, learn,

or be healed or rescued comes along! He may be the answer to Shakespeare's

Jacques (All's Well That Ends Well!), and may it be said that all does end

well for Dr. MacNeill. His marriage strongly affirms his connection to the

mission and his community. He can leave behind the desolation of his cabin

as it becomes a home, and his marriage, unlike his education, may unite him

to his community forever as well as to Christy.